Part 2 of 4

“Baseball people generally are allergic to new ideas. We are slow to change.” Branch Rickey

From the beginning it could be said that numbers are in baseball’s DNA. The importance of numbers in evaluating men playing the game has always been present. After all, measuring talent is the difference in winning and losing and how we grade each generation of players with the preceding one. More than any team sport, baseball is built on individual performance which contrasts with the interdependence of other team sports. This allows a precision of numbers to flow from it that can be critically examined.

Is the study of baseball numbers a modern construct? Section I gave us hints of baseball’s data science prior to the SABR revolution, but let’s look at some of the early pioneers who chartered the course with numbers but understood the role of intuition in baseball.

Baseball’s English Father

In Chapter One, Henry Chadwick is quoted as saying, “In time, the game will be brought down almost to a mathematical calculation of results from given causes.”

Chadwick, who Branch Rickey designated as one of the two most important “immortals” of the game in his book, The American Diamond, A Documentary of the Game of Baseball, was born in England in 1824 before migrating to the United States in 1837. His importance stems from his ability to write about the early days of baseball, in fact, he was the game’s first writer, statistician, general voice and overseer.

In 1858, as a New York sportswriter, Chadwick invented the modern box score, the all-important scorekeeping entry that memorializes games. Box scores were immediately embraced by the public as an organized accounting of players and plays, a small snapshot, if you will, of game summaries. The Englishman was the first to award hitters a “base hit” when they hit their way on base but did not score. His innovations with game records also included “total bases” and “unearned runs”. While box scores had appeared 13 years prior, Chadwick made it the Bible of baseball, the official tally of action on the field which revealed scientifically that baseball was a symphony of numbers.

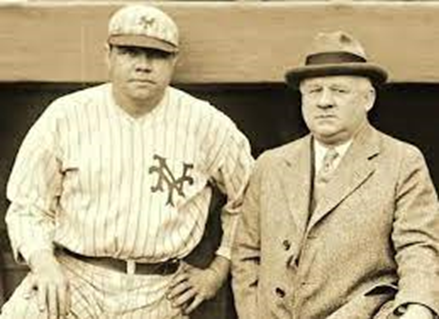

Big Mc

As Chadwick laid the foundation of infusing the game with numbers via box scores, early baseball pioneers were organizing to find advantages. Baseball Hall of Fame (1937) player and manager, John McGraw whose career in baseball touched 5 decades beginning in 1891, was an early proponent of using intellect to dissect games. In fact, McGraw claimed his preference of college players because they had a better work ethic and tried to “fix their faults” as opposed to uneducated players who try to hide their faults.

During baseball’s “Dead Ball Era” McGraw cultivated the scientific game with close examination of speed, defense, and pitching to construct his teams. In 1913, he authored Scientific Baseball, a popular book ahead of its time with a statistical summary of the 1912 season. He was the master of “Inside Baseball”, a term used to mean a highly specialized knowledge about the game. The use of singles, bunts, walks, and stolen bases in place of power hitting was at the heart of Inside Baseball and McGraw was the Master of It having played under its discipline when he was with the Baltimore Orioles. Later as a manager, he built rosters with players that fit his model of game science that exploited the suicide squeeze, hit-and-run, and the Baltimore chop which led to winning 10 pennants, 3 World Series, and over 2,700 games.

The Mahatma

One of the game’s greatest innovators was the already noted Branch Rickey. Most recognized for his social impact on America when he signed Jackie Robinson to break the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” in 1947, Rickey was a highly regarded baseball mind. His playing career as a catcher from 1905 to 1913 was below average, but his managerial and front office years were exceptional.

From 1913 to 1962 Rickey began his shrewd assault on the game by pioneering the minor league farm system and as head of the Brooklyn Dodgers he reshaped MLB spring training by creating Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida. Interestingly, it was at Dodgertown that Rickey began the practice of having players use batting helmets and constructed netted batting cages for hitting refinement. Hitting tees and pitching machines followed and soon the way players were instructed and analyzed began to change player development. But it was Rickey’s fascination with numbers and his early move toward data collection that is often overlooked.

Almost twenty years prior to Earnshaw Cook’s Percentage Baseballset the stage for the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR), Rickey was applying math equations to the game.

The year 1947 was a seminal year in baseball on two fronts, Jackie Robinson was pounding discrimination with each swing of the bat, and Allen Roth was pounding chalk boards using advanced calculations to assist in a new baseball science.

When Rickey hired Roth to be a full-time statistician for the Dodgers it was a first for MLB. Roth’s analysis combed over each hit, run, and pitch with results that impacted the way the Dodgers played the game and maneuvered player acquisition. Early on, Roth understood that batting averages didn’t measure disciplined hitters, but by adding hits with walks and dividing by at bats, the ”on-base percentage” was born. Roth also was the first to recognize the statistical values of right-handed hitters matching better with left-handed pitchers and vice versa, thus “platooning” certain players in lineups became common place.

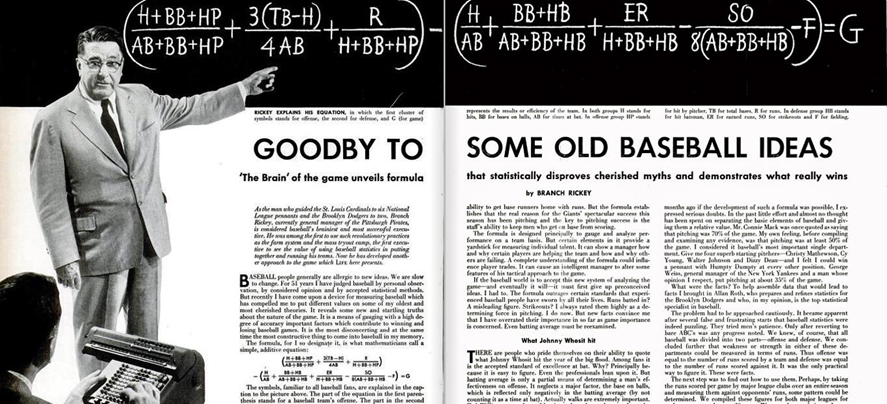

By 1954, Rickey outlined the statistical work the Dodgers had embarked upon in an article for Life magazine titled, “Goodby to Some Old Baseball Ideas.”

“…I have come upon a device for measuring baseball which has compelled me to put different values on some of my oldest and most cherished theories. It reveals some new and startling truths about the nature of the game. It is a means of gauging with a high degree of accuracy important factors which contribute to winning and losing baseball games.”

The “device” Rickey referenced is known by mathematicians as a “simple, additive equation”. Here is how the Dodgers applied it:

(H + BB + HP + 3(TB-H) + ___R______)

AB + BB + HP 4AB H + BB + HP

__ (_H_ + BB + HB____ + __ER_____ __ ___SO___ -F) + = G

AB AB + BB + HB H + BB + HB 8(AB + BB + HB

The first part of the equation represents offense while the second part defense. The difference between the two represents a team’s efficiency. Overall, the Dodgers believed it was a scientific way to determine strengths and weaknesses in place of traditional baseball wisdom. Apparently, the math added up because from 1947 to 1956 the Dodgers made it to the World Series six times. Of course, Rickey left for Pittsburgh in 1951, so addition by subtraction could be in the equation.

An interesting conclusion to the article quotes Rickey as saying that MLB executives would “accept this new interpretation of baseball statistics eventually.” He was right. As for Roth, Bill James is on record as saying,

“He was the guy who began it all.”

THE CLASH

In April 2019, The New Yorker magazine published an article written by Louis Menand titled, “What Baseball Teaches Us About Measuring Talent”. The piece details the “clash between data and intuition” and how the debate inside the game is more about tradition and modern advancement. Menand uses Christopher Phillips’ book, Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know About Baseball to frame the discussion. It’s interesting to note that Phillips believes that baseball opens the door to a much larger conversation about evaluating human beings in a modern society. In that context, Phillips describes the battle as one between “scout-versus-scorer”.

To the “scorer”, quantifying production is central to the science of measurement and assigning value. To the “scout”, observation is more valuable when assigning values. Included in Menand’s article is an important observation from Michael Lewis, author of the forementioned Moneyball:

Lewis’s “scorers” are geeky Harvard grads who speak stats-talk and who actively disidentify with the culture of the game. Their whole approach is based on disdaining the wisdom of the scouts. They don’t need to see prospects, they don’t even need to see games, because, for them, a player is not a body; he’s a row of numbers.”

While both are at odds and seek to dominate the process of evaluation, neither gives quarter to the other. Thus, placing a tidy bow on the divide is useful if we are to understand how the game has evolved (or devolved).

Because technocracy finds new heights in the construction of baseball at all levels, let’s dig into the world of the scorer and how these information scientists have usurped the traditional scout whose “primitive theology” is akin to superstition.

NEXT (PART 3): TRUST THE SCIENCE

Leave a Reply