Part 4 of 4

“Science, like any other human aspiration, is liable to self-deception. If we are uncritical we shall always find what we want: we shall look for, and find, confirmations, and we shall look away from, and not see, whatever might be dangerous to our pet theories.” Karl Popper (philosopher)

During World War II, two men (John L. Barker Sr. and Ben Midlock) developed radar for the U.S. military while working to solve the specific problem of terrestrial landing gear damage to amphibious aircraft. Their work with soldered coffee cans turned into the science of Doppler radar and was used to measure the sink rate of landing sea craft. By 1949, state police in the northeast saw radar as an effective device to enforce speed limits, and little more than a decade later radar guns were included in the public lexicon.

In 1973, Michigan State baseball coach, Danny Litwhiler saw campus police use radar to time speeding cars. Litwhiler, already known as the first player to sew the fingers of a glove in 1942, saw the potential to use radar guns as teaching tools for baseball to measure the velocity difference between fastballs and changeups.

He contacted the JUGS Company, known for making pitching machines, and soon work on hand-held radar devices for pitching was created.

Today, radar is a key tool in fan engagement as 100 mph pitches explode on scoreboards to the delight of tech savvy crowds. The availability of radar in modern America is as simple as an app connected to smart phones and includes the ability to integrate it with video and training data. Radar’s widespread use continues unabated at all levels in baseball including Little League, yes, Little League!

Star Wars

When MLB unleashed PITCHF/x (a system that tracks the speeds and trajectories of pitches) in 2006, it marked a new direction for Doppler technology in baseball. No longer was radar relegated to handheld guns with simple number readouts, instead, data became optical. The PITCHF/x system (using two mounted stadium cameras) created the ability to track not only velocity but the release point, movement, spin, and pitch location for each thrown pitch to a level of detail never seen before. It also introduced a virtual box used by television producers to show a pitch inside or outside the strike zone, which is now an important part of watching a game.

By 2014, MLB took the science of measurements to new heights when it installed Statcast in some of its stadiums. Like PITCHF/x, Statcast, is a high speed, automated system that is very accurate and used to analyze player movement and game action. While PITCHF/x took the science of Doppler radar and turned it upside down, Statcast built a new layer by adding high-definition video. Now, the ability to analyze velocity, trajectory, break, spin, and location of pitched baseballs along with hit distance, exit velocity, launch angles, and hang times of batted baseballs create a prism carnival ride for the game.

More Please

So, did we really need 6-minute abs once we found 7-minute ab workouts? Baseball said yes. Hawk-Eye (Statcast’s second-generation sister)uses an advanced optical-tracking and vision-processing system which affords a continuous data stream on all plays in the field. This 21st Century marvel gives incredible insight into pitcher/hitter mechanics, pitcher deliveries, trajectory of balls leaving the bat, and a lot of defensive metrics that pinpoint the good and bad of players.

The traditional game once measured by simple batting averages has given way to an incredible cafeteria of game information. No longer does baseball rely upon a scout’s ability to identify the sound of a ball hitting a bat, the new standard measures that sound in science fictionoptics.

The race to quantify movements within the game using automated camera and data capture technology has witnessed other high-tech systems push for their turn at bat; TrackMan, Blast Motion, Rhapsodo, Hit Trax, Yakkertech, Modus, Edgertronic, and Senaptec have all turned player performance into quantifiable science. The key takeaway is that advanced measurement technology allowed hard science the ability to create scalable systems that have changed how baseball is managed, analyzed, and consumed.

Back to the Future

As outlined, baseball media has found treasure in eye-popping graphics of tape measure home runs and defensive path angles which are calculated on screen. These new technologies have even introduced a new language to better communicate the integration of science with baseball.

| TERM | MLB.COM DEFINITION |

| Exit velocity | “The speed of a baseball after it is hit by a batter.” |

| Launch angle | “The vertical angle at which the ball leaves a player’s bat after being struck.” |

| Catch probability | “The likelihood that a batted ball to the outfield will be caught.” |

| Spin rate | “The rate of spin on a baseball after it is released.” |

| Barrel | “Assigned to batted-ball events whose comparable hit types (in terms of exit velocity and launch angle) have led to a minimum .500 batting average and 1.500 slugging percentage.” |

While engaging fans has always been a high priority for baseball executives, the ability to use measurement technology to better define a player is the real value for technocrats running player development. The use of high-end technologies has and continues to change the way hitters and pitchers are recruited, instructed, and evaluated. Technocracy welcomes these advances and uses them to cross the traditional Rubicon of observation.

Exit Signs

Two early proponents of using measurement technology in player identification were the Tampa Bay Rays and the Houston Astros. The Rays told their players on the first day of spring training in 2015 that their performances would be evaluated based on hitter exit velocities. In 2017, the Astros under general manager, Jeff Luhnow incorporated over 70 Edgertronic cameras inside their organization at a cost of more than $350,000. Using seven cameras per stadium, the Astros were interested in identifying player biomechanic analysis using artificial intelligence known as “computer vision”. This allowed computers to interpret the images collected by the cameras to better understand player movement in space.

The Interrogation of Influences

Placing the game under a computer microscope continues with over 70 individual statistics analyzed per game in baseball and there is little to suggest that science and baseball are slowing in their torrid love affair. As the interrogation of influences grows, how long before we discover pitcher pulse meters and sweat gland data of hitters in high leverage situations? With faster in-game propositions offered by sports betting companies, do you think gamblers would be interested in whose heart is pumping faster in a 3-2 count, the pitcher or the hitter? But let’s not get too far ahead in our conversation.

Ground Control to Major Tom

In 2016, the Houston Astros made a small splash by hiring a soccer consultant inside their sports science department. Jose Fernandez was an experienced European soccer mind fresh from Barcelona, Spain and its soccer giant, FC Barcelona.

According to Travis Sawchic of FiveThirtyEight.com, Houston was intrigued by the centralized training centers used by the best soccer franchises. What Fernandez emphasized was the “La Masia” or “Farm House”, a central campus to build skills as opposed to a decentralized affiliate system spread across many locations. Sawchic quotes Fernandez as saying:

“On site in Barcelona, they have their whole development academy, from the kids all the way up to the professional teams. They have one big campus. They do everything on-site. Everything is coordinated. Everyone is doing the same drills. Everyone was being measured with the same technology.”

The following year, the Astros reduced their affiliates from nine to seven. It was an innovative and risky move for baseball, not since the modern minor league system had been put in place by Branch Rickey in 1919 had a baseball team pivoted to actively rethink player development. Surely the Astros didn’t decide to reduce its minor leagues and the fallout that goes with it because some guy from Spain said this is how soccer does it, right?

Science To the Rescue

When the Astros signed Fernandez they were nearing the end of a rebuild under previously mentioned general manager, Jeffrey Luhnow. A well-versed technology entrepreneur, Luhnow was initially hired by the St. Louis Cardinals in 2003 to provide data analysis similar to what the Oakland A’s had established under general manager, Billy “Moneyball” Beane. Despite limited baseball experience, the Cardinals had taken a chance on Luhnow to overhaul the organization using data analytics. It turned out to be successful as his first order of business was to upgrade the organization’s ability to capture and analyze data and to restructure their international and domestic scouting efforts.

By 2006, Luhnow’s star was rising as the Cardinals promoted him to vice president of scouting and player development. Not bad for the Mexico City native with a resume that includes global management consultants, McKinsey and Company and a stint as CEO of Archetype Solutions. By the time of Luhnow’s departure in 2012 for greener pastures in Houston, he was responsible for tremendous success in the Cardinals farm system that included five minor league championships.

During his first three drafts in St. Louis, 24 major league players were identified, which is tops for all organizations in that window. Several players selected by Luhnow played key roles in the 2011 World Series victory over the Texas Rangers. His success in St. Louis quickly made him a hot commodity in the front office carousel at the beginning of the 2012 baseball year.

How did Luhnow, with little to no baseball background, rise to general manager of the Houston Astros in less than ten years? New York Times writer, Tyler Kepner sheds some light when he quotes Luhnow in his January 2020 article titled “The Rise and Sudden Fall of the Houston Astros”:

“It’s not an issue of just crunching numbers,” (Luhnow) said. “It’s an issue of collecting and evaluating and interpreting and using information across a whole bunch of disciplines that allows you to take the most educated guess you can as to how that player’s going to perform in the future. And if we can do that 5 percent better than the rest of the clubs, that’s a significant edge in our game.”

Digging deeper, Luhnow a graduate of the prestigious Wharton Business School with B.S. degrees in engineering and economics, put together a plan to reconstruct the Astros like the Cardinals. His strategy was an unorthodox one. He hired non-baseball experts like Kevin Goldstein an acclaimed writer from Baseball Prospectus as Pro Scouting Coordinator as well as Brandon Taubman, an investment banker with Barclays whose expertise was in equity derivatives. The previously noted Sig Mejdal, a close ally with Luhnow while in St. Louis was given the title of Director of Decision Sciences. He also hired an economist and an MBA to help maximize Houston’s payroll and resources. Soon, the focus became the integration of analytics, technology, and business in a seamless baseball algorithm.

Four-Part Plan

To accomplish the desired data-driven results, the Astros put in place a four-part strategy. Number one, build with data analytics using detailed data questions and driven by camera technology. Specifically, power and speed were explored and quantified. Number two, integrate scouting and player development with personnel that could identify players with the results number one was suggesting. Then employ coaches that could change mechanical movements that were problematic for the player identified. Number three, use cutting-edge technology and innovation (cameras again) to target skills players can improve upon. And number four, maximize player performance through innovative sports medicine. Luhnow’s focus was to personalize individual workloads and intensities to improve performance and to measure areas of injury risks.

Ultimately, Houston’s infrastructure was breaking new ground by measuring every data point on the field. In fact, by 2019 the Astros (as noted) had installed 75 high-speed cameras throughout their system to assist players in recognizing performance enhancing biomechanical movements collected frame by frame. Of course, using cameras to better the organization took a dark turn when it was discovered they had been used to steal signs from opposing teams, but that doesn’t take away from Luhnow’s commitment to technocracy which MLB has wholeheartedly embraced.

For those interested in the deep dive associated with the Astros game altering rise and fall under Luhnow, I suggest you pick up a copy of Winning Fixes Everything by Evan Drellich.

As the Astros embarked on a modern space-age exploration inside the game, they began to discover that many players in the organization couldn’t meet the demands used to construct the four-part plan. Thus, they believed they were supporting a lot of players that had a very low percentage chance of making it to the majors. The decision then became to direct coaching resources to those that their baseball science suggested could make it.

Frankenstein In Cleats

Beginning in 1965, Major League Baseball initiated its first-year player draft as an organized attempt to assign amateur players from high schools and colleges to its teams. Prior to 1965, all amateurs were free to sign with any MLB club that offered them a contract. The draft system was supposedly in response to larger market teams with more resources that were able to stockpile talent at the expense of the smaller market teams. But it was just another version of the 1947 Bonus Rule that took aim at growing player salaries and an attempt to reduce the monopolization of baseball by big market teams.

When the ’65 draft began, there were 824 players selected. Each subsequent year, MLB would decide on the number of rounds to be included in its June first-year player draft until 50 rounds representing 1,400 players became the standard in 1998. Later, MLB reduced the rounds to 40 in 2012 where it remained until the global health crisis in 2020 cut the draft to 5 rounds and later back up to 20 rounds in 2021.

Baseball By Numbers

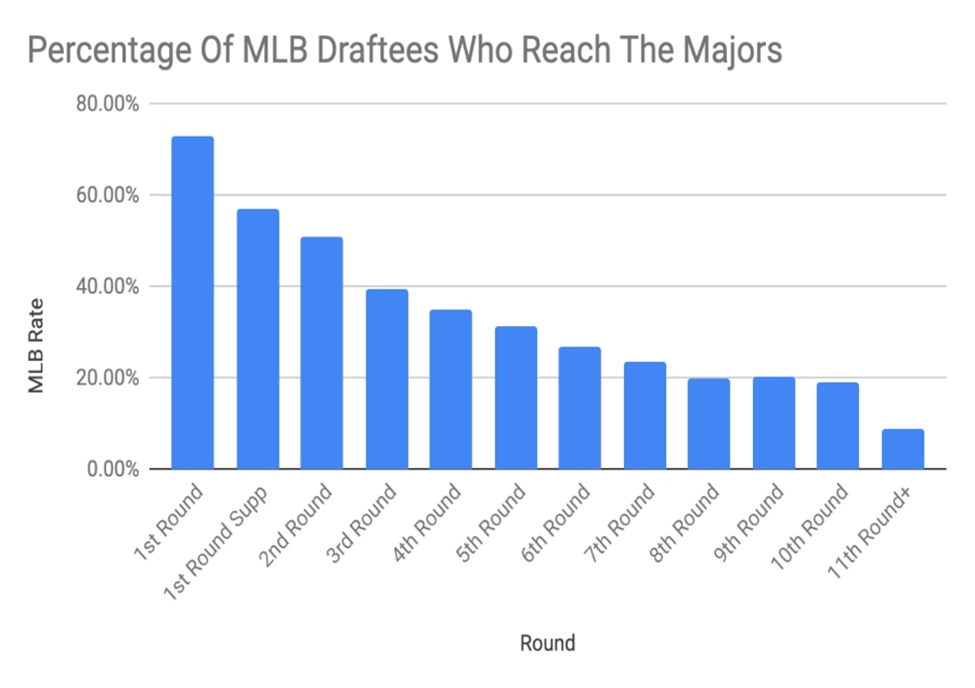

In May 2019, Baseball America posted an article titled: “How Many MLB Draftees Make It To The Majors”. The respected baseball publication tallied numbers from 1981 through 2010 and found that only 17.6 percent of players drafted and signed ever made it to the majors. But BA noted that there was a sliding scale to their data with 73 percent of first-round picks, 51 percent of second-round picks, and 40 percent of third round picks eventually making it to the “show”.

The data was harsh for players selected after the 21st round with only 7 percent ever appearing in a big-league game. The Luhnow led Astros connected the dots and scientifically questioned the need to employ 83 percent of its minor league player payroll that would never compete at the major league level. The Astros believed their four-part plan understood potential better and needed less time and fewer games to realize the wanted results. Thus, they believed consolidating resources around the most promising players was more efficient and cost saving.

But the Astros plan couldn’t be near as effective if the balance of MLB teams continued to have more players and minor league operations, after all, there is power in numbers even if the science of numbers was on the Astros side. As Houston exalted the virtues of less is more with others, the Astros plan took root when MLB ledgers showed the estimated millions in savings by employing technology over humans. Apparently, cameras and computers don’t require health plans and pensions.

No Minor Change

By 2019, MLB was openly signaling a new restructuring of all minor league operations when commissioner Rob Manfred went on record in a July 2019 interview with online sports publisher, The Athletic and said:

“We have to look at the efficiency of the [minor league] system that we’re running right now, how many teams, how many players, what we’re paying players, and all those issues are obviously related.”

The monster built by Earnshaw Cook and his band of baseball scientists over the course of half a century had come to life and was now ready to be unveiled to the world under the guise of MLB’s “One Baseball Policy”.

More about that next time….

Leave a Reply