Part 4 of 4

This is the fourth and final part of a four-part series covering the potential impact of velocity and arm injuries.

COUNTING BACKWARDS

As reduced workloads continue to determine any meaningful conversation relating to the health of pitchers in the modern era, it’s important to examine the impact of pitch counts and inning limits. At the heart of pitch counting is the need to avoid excessive stress to arms.

In 1998, a baseball analyst named Rany Jazayerli created a system to measure risk factors of pitchers due to repetitious high workloads.

His “Pitcher Abuse Points” (PAP) system focused on the hypothesis that, throwing is not dangerous to a pitcher’s arm, throwing while tired is. Thus, his PAP’s were structured to monitor pitches after the 100 pitch plateau along with the age of the hurler. His hope was to capture fatigue ratios as a pitcher reached higher game workloads. His pitch count scale would quantify the effect of arm strain as a pitcher increases his pitches in a game.

Pitches 1-100 = No PAP awarded

Pitches 1-100 = No PAP awarded

Pitches 101-110 = 1 PAP per pitch

Pitches 111- 120 = 2 PAP per pitch

Pitches 121 –130 = 3 PAP per pitch

Etc….

Finding data that would quantify the correlation between the number of pitches thrown tired and injuries seemed simple, after all, when pitcher mechanics break down through fatigue, muscles become sore and the body responds adversely to the stress required for additional pitches.

The premise was simple, fatigue sets on gradually and each continuing pitch increases the danger to the pitcher.

Jazayerli was on track, but ultimately, his research didn’t find the necessary links between pitcher injuries and PAP because pitch counts are narrow in scope.

Counts don’t reveal velocity, arm angle, or kinesiology, rather they serve only as a blank chamber for those expecting a silver bullet answer to injury.

But, PAP’s did garner the attention of MLB which systematically began the reduction of 130-pitch starts. In fact, as I mentioned earlier, “In 2017… only 18 games out of 4,860 played witnessed a starter throw more than 120 pitches in an outing! That’s in comparison to…1988 when 597 games recorded a pitcher with over 120 pitches in a game…”

Dr. Thomas Karakolis, a scientist at Defence Research and Development Canada and formerly of the University of Waterloo, was quoted from a Reuters Health study that examined the correlation between pitcher injuries and pitch counts and innings pitched:

“I don’t necessarily think that pitch counts or innings pitched are the best way to measure the demands of pitching.” He went on to add, “Injury is the result of workload exceeding the capacity of the body’s tissues, so while counting innings is a tempting way to measure workload, it’s actually a very flawed method… If coaches are looking for ways to prevent injury, simply limiting the number of innings is not the answer. They have to look at how hard a pitcher’s body is working each inning, each pitch.”

If Dr. Karakolis is on target, perhaps the conversation should shift to fatigue and training.

BEAST MODE

Training regiments for pitchers in today’s MLB is dependent on the philosophy of each organization. I know of one American League team that has historically refused to allow their pitchers to use weights and have perennially had a low number of their pitchers on the disabled list (DL).

Training regiments for pitchers in today’s MLB is dependent on the philosophy of each organization. I know of one American League team that has historically refused to allow their pitchers to use weights and have perennially had a low number of their pitchers on the disabled list (DL).

But, in the high dollar world of professional baseball, more have turned to science to determine their training guidelines.

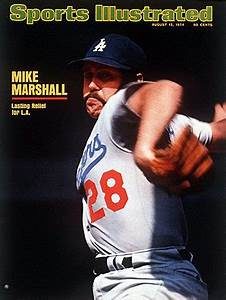

Dr. Mike Marshall has studied and used kinesiology to break new ground in the quest to find answers relating to pitcher movements since he began professional baseball in the 1960’s. His research allowed him to win the Cy Young Award in 1974 as the game’s top reliever while playing with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Ironically, Marshall was on the same staff that forged the new five-man rotation in which Tommy John was a part.

As a true pioneer in bridging the gap between kinesiology sciences and pitching performance, Marshall mastered Isaac Newton’s laws of motion with applied force principles as it relates to the human body on a pitcher’s mound.

Dr. Marshall’s incredible devotion to science paved the way for today’s advances in unlocking answers to arm injuries. His uncompromising and unorthodox approach to pitching deliveries is a journey reserved for true baseball engineers. While kinesiology study remains central to unlocking arm injuries, technology has forced its way into the conversation.

SPORTS SCIENCE

In northern California, in the technology capital of the United States, Sparta Science captures the 21st Century approach started by Dr. Marshall. This company applies data and technology to athletic performances in order to create what they term “motor signatures“.

These signatures are then analyzed in computer programs individually modified to identify neuromuscular obstacles for the athlete. Already, the Colorado Rockies and the San Diego Padres have subscribed to the Silicon Valley approach and believe Sparta best captures the science of force in order to identify weaknesses that can prevent injuries.

But where is Major League Baseball in the hunt for answers?

MLB has partnered with American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) to use science to better understand arm safety. ASMI was founded by noted orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews, who has performed surgeries on some of baseball’s top pitchers since the 1980’s.

ASMI’s research has studied the history of injuries for pitchers, mechanics, genetic dispositions, pitch counts and velocity in order to better understand core issues surrounding arm health. One of the more intriguing issues MLB has asked ASMI to research is the impact of lowering pitching mounds from the current 10 to 6 inches.

BACK TO 1968?

Would lowering the mound 4 inches improve the health of pitchers or offset the burgeoning velocity religion and its effect on hitters? Or Both? After all, dropping the mound 5 inches in 1969 had a significant impact as overall ERA jumped from 2.99 in ’68 to 3.59 in the ’69 National League while the numbers in the American League were similar, 2.98 to 3.62. Of course, I’ve already outlined the struggle to score runs to keep stadium seats full.

It doesn’t take a team of scientists to understand that throwing baseballs off smaller hills reduces velocity. But, former MLB pitcher and current Dodgers pitching coach, Rick Honeycutt is on record saying that the steeper the grade of the mound the more “stretched out” a pitcher becomes before his foot hits the ground and the more of the impact of throwing a pitch is absorbed by the lower body. His thought is that with a limited grade (smaller height), the contract between the foot and mound comes quicker leading to a greater impact on the shoulder area when releasing a baseball. Hall of Famer, Nolan Ryan agrees. “I always felt I had better leverage with a steeper mound, and it made a difference on the velocity of the fastball and break of the curveball. He added, In the days of higher mounds, “the injuries were not a as prevalent as they are now.”

It doesn’t take a team of scientists to understand that throwing baseballs off smaller hills reduces velocity. But, former MLB pitcher and current Dodgers pitching coach, Rick Honeycutt is on record saying that the steeper the grade of the mound the more “stretched out” a pitcher becomes before his foot hits the ground and the more of the impact of throwing a pitch is absorbed by the lower body. His thought is that with a limited grade (smaller height), the contract between the foot and mound comes quicker leading to a greater impact on the shoulder area when releasing a baseball. Hall of Famer, Nolan Ryan agrees. “I always felt I had better leverage with a steeper mound, and it made a difference on the velocity of the fastball and break of the curveball. He added, In the days of higher mounds, “the injuries were not a as prevalent as they are now.”

GOLDEN RULE?

Again, is affecting velocity the golden answer to keeping pitchers healthy? Noted baseball writer, Buster Olney penned a column in which he gave statistical analysis of 328 occurrences of pitchers spending time on the disabled list (DL) in 2018. This represented 37 more pitchers on the DL than in 2017 and 88 more than in 2015! He quotes an MLB scout who believes that max effort pitching has led to increase in blister problems. Blister problems? Apparently, pitchers are vulnerable to a host of ailments outside the vagrancies associated with elbow valgus. Just look at the myriad of pitchers who started the season on the DL with injuries:

*Madison Bumgarner, SF, pinky fracture

*Madison Bumgarner, SF, pinky fracture

*Eduardo Rodriguez, BOS, left knee surgery

*Ervin Santana, MIN, finger surgery

*Zach Britton, BAL, ruptured Achilles

*Jeff Samardzija, SF, pectoral strain

*Drew Pomeranz, BOS, forearm strain

*Danny Salazar, CLE, right shoulder inflammation

*Luiz Gohara, ATL, groin strain and ankle strain

*Dinelson Lamet, SD, flexor strain

*Adam Wainwright, STL, hamstring strain

*Anthony DeScifani, CIN, left oblique strain

It’s interesting to note that 39% of all starting pitchers will end up on the DL the following season after being a starter in the league the year before. And the cumulative effect will result in an average of over 66 days lost. On average, teams now expect 10 different pitchers will start games for each organization during the 162 game MLB calendar. Its impact is not to be understated. In fact, some estimates according to Hard Ball Times writer, Jon Roegele suggest $850 million in salaries were paid to pitchers who were unable to play due to Tommy John surgeries and subsequent recovery periods up to 2017! That’s just TJ surgery hurlers.

According to former Reds manager Bryan Price,

“(Pitcher injuries) is an industry issue. We haven’t solved the problem. There are more days lost to the DL… You see oblique and intercostal strains. There are just a lot more injuries that are more common than ever… We’re trying to define what causes it. I don’t want to say we’re grasping at straws. There are smarter people than me looking at this. We are one of many organizations that have struggled to keep pitchers healthy.”

Until now, my focus has been the impact of arm injuries relating to MLB and players in the United States. But, what about other countries and how they manage arms?

BONZAI

The Nippon Professional Baseball Organization (NPB) is Japan’s highest baseball league. Its roots trace back to 1934 Tokyo where the love of the game survived its dark entry into several war theaters through 1945. The NPB rules are like MLB but the baseballs are smaller as are playing fields and strike zones. The level of play has been described as higher than AAA but lower than MLB, thus AAAA.

The Japanese have historically used a six-man rotation as opposed to MLB’s five-man rotation which allows for an extra day of recovery for the pitcher. Because pitchers have more rest, Japanese coaches place less emphasis on pitch counts knowing their pitcher will have ample time prior to his next start. The suggestion becomes Japanese pitchers who have made the jump to MLB have had difficulty adjusting to American baseball because of the five-man demands with less recovery time. But, perhaps NPB rules which restrict players from playing outside Japan until they have the required nine years of professional experience, plays a role as well. Thus, the backdrop for Japanese players “posted” for international free agency have already passed “peak arm” age (27) and are more vulnerable to wear and tear in professional America.

But, lets dig a little deeper.

Analyzing workloads among Japanese pitchers in their high school window could add to the conversation since they’re known to have high demands placed on them. In fact, the saying in Japan is:

Eggs thrown at the wall that don’t break are called superstars. And the true superstars are called “Kaibutsu” or Monster.

So ingrained in the psyche of Japan’s pitchers to become Kaibutsu that they adhere to regiments of excess that are incredible.

Daily throws into the hundreds without taking a day off. Even pre-game bullpens several hours before game time that can reach over 100 pitches are normal. This pregame dynamic is defined by warming the body and using extended stretching before ever picking up a ball. The Japanese also incorporate weightlifting for strength and not bulk while paying attention to connecting muscle groups. The use of hot and cold soaking along with massage is part of the recovery phase emphasized with their trainers and coaches. It all leads to a culture that prepare pitchers for extreme workloads because the Japanese equate pitch counts with superiority. Enter Summer Koshien.

SUMMER KOSHIEN

Historically, high school pitchers have become legends for their exploits in Japan’s National High School Baseball Championship, called the Summer Koshien. This rite of summer passage dates back 100 years as prep teams from across the nation descend on Hanshin Koshien Stadium in Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture. The two-week tournament involves 49 teams from the 47 prefectures (government districts) in Japan that won their qualifiers. This unofficial national festival often hosts crowds of up to 50,000 fans per day, while each game will be telecast live, nationwide, by NHK to millions of viewers.

Stardom and even immortality await those who excel in the Summer Koshien. Daisuke Masuzaka (Boston) and Masahiro Tanaka (NYYankees) are two who carved out such special recognition. As a prep star in Japan, the “gyro ball” architect, Matsuzaka threw a 148-pitch shutout to begin the Koshien in 1998. The next day he threw 250 pitches in 17 innings in the quarterfinal. The following day he started in the outfield before entering in relief as his team overcame a 6-run deficit to win. He then threw a no-hitter in the championship to solidify Koshien immortality! Overall, he threw more than 500 pitches in the tournament.

Current Yankees ace, Tanaka threw 742 pitches in over 52 innings during the 2006 tournament. But, both Tanaka and Matsuzaka pale in comparison to Yuki Saito, who pitched 69 innings with a pitch total of 948! This year’s Koshien witnessed Kanaashi Agricultural High School pitcher, Kosei Yoshida deliver 881 pitches over 50 innings during six appearances. With known examples of extreme workloads within Japan’s baseball culture, surely arm injuries in the land of the rising sun are more prevalent, right?

Current Yankees ace, Tanaka threw 742 pitches in over 52 innings during the 2006 tournament. But, both Tanaka and Matsuzaka pale in comparison to Yuki Saito, who pitched 69 innings with a pitch total of 948! This year’s Koshien witnessed Kanaashi Agricultural High School pitcher, Kosei Yoshida deliver 881 pitches over 50 innings during six appearances. With known examples of extreme workloads within Japan’s baseball culture, surely arm injuries in the land of the rising sun are more prevalent, right?

TOMMY IN ASIA

The previously mentioned Dr. Glenn Fleisig of the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) is on record when asked about the impact of workloads associated with Summer Koshien. In 2013, Dr. Fleisig was asked by Yahoo! Sports writer, Jeff Passan about the accumulation of pitches by then 16-year-old pitcher, Tomohiro Anraku, who pitched a total of 772 pitches in the Koshien.

“(It’s) completely off the charts…It goes against everything we do in sports medicine in America. There’s talk about how things are done differently in Japan, which clearly they are. But humans are still humans. It doesn’t make any sense. Is an 80-pitch count perfect or 120 or three days’ or four days’ rest? There’s no perfect number. But it’s inconceivable this can be reasonable.”

By the last game, Anraku, whose fastball reached 94 mph earlier in the tournament, struggled to touch 80.  Considering It was the youngster’s third consecutive day starting a game and fourth in five days is remarkable. And that was after starting the tournament with 232 pitches in 13 innings! “The way humans are built, whether you’re a 16-year-old or an old guy like me, your body needs 48 to 72 hours to recover from muscle fatigue and damage,” Fleisig said. “If you have a big pitching workout or run distance, if you’re fatigued where you have lactic acid and your muscles are sore, you need time to recover.

Considering It was the youngster’s third consecutive day starting a game and fourth in five days is remarkable. And that was after starting the tournament with 232 pitches in 13 innings! “The way humans are built, whether you’re a 16-year-old or an old guy like me, your body needs 48 to 72 hours to recover from muscle fatigue and damage,” Fleisig said. “If you have a big pitching workout or run distance, if you’re fatigued where you have lactic acid and your muscles are sore, you need time to recover.

If you pitch fatigued and come back in a day or two, your damage on your elbow and shoulder will add up. It won’t be new. It’s just compounding… Small damages will add up to big injury. They always do.”

What about quantifying the damage to arms of prep or NPB pitchers? Unfortunately, digging out answers as to arm health in Japanese baseball is difficult to find. Research concerning Tommy John surgery occurrences for Japanese pitchers is limited as well. What little information is available suggests that the numbers are half their American counterparts. But, the Japanese are known to offer little data or science to support their traditions, thus accurate information as to arm health for Nippon hurlers is reduced to whispers.

CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, we are no closer to finding answers to baseball’s biggest question as when the discussion began. There is much more to be considered like advances in Tommy John surgeries as well as understanding the science of injuries.  Or, the impact of performance drugs that continue to plague baseball. But, as long as the demands of the game fall heaviest on the guy on the hill, pitchers will continue to break down. Perhaps, when it’s all said and done, management is the best the game can hope for.

Or, the impact of performance drugs that continue to plague baseball. But, as long as the demands of the game fall heaviest on the guy on the hill, pitchers will continue to break down. Perhaps, when it’s all said and done, management is the best the game can hope for.

Truly, there is no greater mystery in sports than the arm.

PREVIOUS: Tommy’s Got A Gun: The National Pastime Chronology

Leave a Reply